Ancient Warnings: Inuvialuit Flood Stories and Climate Reality

There is a cautionary tale passed down through generations of Inuvialuit, the Indigenous people whose native land stretches from Northern Alaska to the Beaufort Sea in Canada’s Yukon territory. It describes a flood that took place “long ago” that covered the entire world. Sarah Meyook heard the story from Irish Kiuruya, who was born in 1892:

“They say once there was a big flood all over Qikiqtaryuk (Herschel Island). You could see nothing! There was nothing then… (except for) some kind of animal high up there in the lake. Maybe it came from the ocean this animal. They don’t know what it is…”

(Excerpt from Nagy, Murielle Ida. 1994:21. Yukon North Slope Inuvialuit Oral History. Yukon Tourism, Heritage Branch.)

Oral history has long been a critical way of passing down indigenous knowledge. Stories that have survived for hundreds of years often impart something important to listeners – universal truths that help us make sense of the world or advice on how to live a good life. Indigenous stories such as these are powerfully connected to place, in a way that outsiders could never fully understand or appreciate.

Qikiqtaruk: The Rich History of Yukon’s Only Island

The island from the story, Qikiqtaruk (also known as Herschel Island), has both a fascinating and complex history. The name literally translates to “island” or “big island” in Inuvialuktun. While this name may seem simple, it’s actually quite fitting: Qikiqtaruk is Yukon’s only island, and stands alone for miles in the Beaufort Sea.

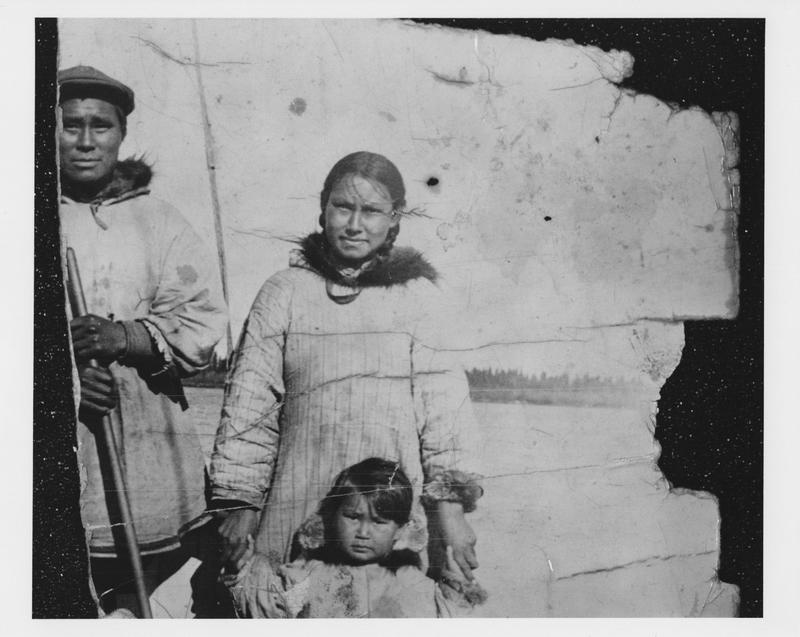

Today, the island is uninhabited except for occasional researchers. Likely to become Canada’s next UNESCO World Heritage Site, it boasts a long history stretching back to the Thule civilization that settled in the region after crossing the Bering Strait. Due to its location and rich spawning habitat, the island served as a seasonal base for fishing and whaling activities for the Inuvialuit people for centuries.

As colonization began in the late 1800s, commercial whaling activity intensified. At its peak in the early 20th century, the Qikiqtaruk community had over 1,500 residents, many connected to the fishing and whaling industries. This thriving community persisted until the decline of commercial whaling, when the population gradually diminished.

Arctic Indigenous Language: When Words for Snow and Ice Mean Survival

While life on Qikiqtaruk revolved largely around fishing and whaling, it would be a mistake to overlook the deeper culture of the Inuvialuit people and their unique ties to the arctic landscape. Among these ties is their Inuvialuktun dialect, famous for its evocative descriptions of the natural world. Inuvialuktun contains over 15 words that distinguish different types of ice and over 20 words that distinguish different types of snow. For example, masak describes wet and waterlogged snow, while piangnaq refers to snow ideal for traveling by sled.

These words for snow and ice are not merely practical distinctions – they are essential for survival in the Arctic. Knowing the difference between masak and pukak (fine snow used for melting into water) could save someone’s life. Language in this sense is not only a carrier of culture but also a tool for survival in an unforgiving environment.

Climate change is now beginning to alter the very language people use, particularly indigenous languages that have existed for centuries. The frequency of piangnaq (ideal sledding snow) has reduced dramatically as temperatures rise. As the environment changes, language is lost as well. In this way, language and culture are inextricably tied to the uniqueness of a place, and cannot be replaced once lost. The erosion of one inevitably means the erosion of the other.

Permafrost Thaw and Flooding: How Climate Change Is Erasing Qikiqtaruk

Climate change has dramatically increased flooding on Qikiqtaruk, endangering what remains of the original community. Much of this flooding can be attributed to the island literally melting away due to the loss of permafrost. As the permafrost on the shoreline thaws, it creates landslides that cause entire chunks of land to fall into the sea. During a two-week stretch in 2024 alone, the island suffered over 700 landslides.

In addition to landslides, the arctic ice surrounding the island has retreated due to longer periods of warm weather. As a result, the island has lost its protective buffer, a critical feature that helped maintain its integrity for centuries. Add in sea level rise, and it becomes clear that flooding will only worsen with each passing year. This understanding of ice offering protection helps explain why it is considered so sacred, and only deepens the collective trauma these communities feel as it is lost.

It would be easy to forget about Qikiqtaruk, given that no one lives there permanently and there is little that can be done to save it. The only real method of preserving the abandoned community is to relocate the historic buildings, but even researchers suggest that these methods are only buying time.

Preserving Cultural Memory: Arctic Digital Heritage Projects

Yet there is hope for keeping the island’s memory alive. Dubbing themselves “technicians of remembrance,” researchers are doing the heavy work of not only documenting a place, but preserving it for future generations. With the help of virtual reality and 3D printing technology, they are recreating the physical landscape that Qikiqtaruk has occupied for hundreds of years, giving future generations the ability to see and experience what it once looked like – all while knowing that preserving the real place in its entirety may be impossible.

These digital heritage efforts remind us that our attachment to place transcends the physical realm. Like our beliefs in life after death, we are motivated by the idea that our places can outlive us. In the end, our hopes, dreams, legacies, and memories may all reside in the places we call home.

What, then, can we humans turn to for answers? What will guide us if we cannot make the changes necessary to preserve this way of life?

When Climate Change Erases Culture: Lessons from Qikiqtaruk

When all else is lost, our stories will hold the treasures we have found along the way. The ending to the story of the flood on Qikiqtaruk is not a cheery one, but it speaks volumes about what awaits humanity if nothing is done:

It is said that after the earth turned over, all the land was covered with water.

This hauntingly beautiful story reminds us that everything – people, land, the earth itself – is connected. That the loss of one place is like losing the entire world, since an entire world can be found in just one place. This idea of mutual destruction echoes across indigenous cultures today, who warn about the collapse of society due to climate change.

Doug Olynyk, a historian from Yukon, captured this tension when he described the despair of people who “won’t be able to experience Herschel Island in its true glory, years from now.”

“But once Manhattan starts being flooded,” he added grimly, “I don’t think people will care about Herschel Island.”

To learn more about the island of Qikiqtaruk and support its addition to the list of UNESCO World Heritage sites, visit the park website here.

Leave a Reply